Enrolling kids in summer music programs can have a multitude of benefits that extend far beyond just learning to play an instrument. At Freeway Music, these programs offer a unique opportunity for children to explore their creativity, develop discipline, and enhance their cognitive abilities. Here are some key reasons why summer music programs are important for kids:

- Creativity and self-expression: Music is a powerful form of self-expression, allowing children to convey emotions, thoughts, and feelings in a creative way. By enrolling in a music program, kids can tap into their creative potential and explore different genres and styles of music.

- Cognitive development: Learning music has been shown to have a positive impact on cognitive development. It can improve memory, enhance mathematical skills, and increase spatial-temporal skills. Music also helps children develop critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

- Discipline and perseverance: Mastering a musical instrument requires dedication, practice, and perseverance. By enrolling in a summer music program, kids learn the value of hard work, discipline, and patience. These qualities can transfer to other areas of their lives, helping them excel academically and professionally.

- Social skills and teamwork: Many summer music programs involve group activities, such as playing in a band or orchestra. These experiences teach children valuable social skills, such as collaboration, communication, and teamwork. Kids learn to listen to each other, compromise, and work together towards a common goal.

- Confidence and self-esteem: As children develop their musical skills and see their progress over the course of a music program, their confidence and self-esteem grow. Performing in front of an audience, whether it’s a small group of parents or a larger concert hall, can help kids overcome stage fright and build confidence in themselves.

- Cultural appreciation: Music is a universal language that transcends cultural boundaries. By enrolling in a music program, kids have the opportunity to explore music from different cultures and time periods. This can broaden their perspectives, foster appreciation for diversity, and spark a lifelong love of music.

Overall, enrolling kids in music programs, especially starting in the summer, when they have less on their plate, can have a lasting impact on their personal, social, and academic development. Whether they continue to pursue music as a career or simply enjoy it as a hobby, the benefits of music education are undeniable. If you have the chance to enroll your child in a summer music program, seize the opportunity to help them unlock their full potential and foster a lifelong passion for music.

Learning to play a musical instrument is a journey filled with excitement, challenges, and, most importantly, patience. For children embarking on this adventure, the concept of patience might seem elusive amidst their eagerness to master the instrument quickly. However, understanding the importance of patience in this process is essential for both parents and educators alike.

Patience serves as the cornerstone of a child’s musical development, fostering a positive and enriching learning experience. Rather than focusing solely on achieving immediate results, cultivating patience allows children to embrace the journey of learning an instrument, nurturing their creativity, and building a lifelong passion for music.

One of the key aspects of fostering patience in children learning a new instrument is encouraging them to “play” rather than “practice.” This subtle shift in language can have a profound impact on a child’s perception of the learning process. By framing their musical exploration as play, children are invited to approach the instrument with curiosity, imagination, and a sense of freedom. This mindset shift empowers children to explore the instrument at their own pace, experiment with different sounds, and express themselves creatively without the pressure of perfection.

Here are some practical tips for suggesting children to “play” rather than “practice” when learning a new instrument:

- Create a Playful Environment: Set the stage for musical exploration by creating a playful and supportive environment. Encourage children to view their instrument as a tool for creative expression rather than a daunting challenge.

- Embrace Mistakes as Learning Opportunities: Help children understand that making mistakes is an integral part of the learning process. Encourage them to embrace their mistakes, learn from them, and use them as opportunities for growth and improvement.

- Encourage Creativity: Foster a spirit of creativity by encouraging children to experiment with the sounds and techniques of their instrument. Provide them with opportunities to improvise, compose their own melodies, and explore different genres of music.

- Celebrate Progress, Not Perfection: Shift the focus from achieving perfection to celebrating progress. Recognize and celebrate each small milestone along the way, whether it’s mastering a new chord, playing a simple melody, or improvising a short tune.

- Be Patient and Supportive: Above all, be patient and supportive throughout the learning process. Encourage children to enjoy the journey of learning an instrument and reassure them that progress takes time.

By encouraging children to “play” rather than “practice,” we empower them to take ownership of their musical journey, make it their own, and develop a lifelong love for music. Through patience, encouragement, and a playful approach, we can nurture the next generation of musicians and inspire them to unlock their full potential.

Introduction:

In the symphony of a child’s development, music education plays a pivotal role, harmonizing cognitive, emotional, and social growth. As we delve into the orchestration of academic studies, it becomes evident that the influence of music on young minds goes far beyond the notes on a page. Let’s explore the symphonic journey of why music education is not merely a supplemental class but an essential element in the composition of a child’s holistic learning experience.

The Cognitive Crescendo:

Research from renowned institutions such as Harvard and Johns Hopkins has been tuning into the cognitive benefits of music education for years. The brain, akin to a musical instrument, undergoes a transformative tune-up when exposed to the intricacies of music. Studies suggest that children engaged in music education demonstrate enhanced cognitive skills, including improved memory, attention span, and problem-solving abilities.

One notable study, conducted at the University of California, found that children involved in music education showed accelerated development in the areas of language processing and mathematical reasoning. The rhythm and patterns inherent in music seem to create a neural symphony, fine-tuning the brain for more efficient cognitive processing.

The Emotional Overture:

Beyond the realms of academia, music education orchestrates a powerful emotional overture in the lives of children. It serves as a melodic refuge, providing an outlet for self-expression and emotional regulation. Music becomes the soundtrack to a child’s emotional journey, helping them navigate the complex tapestry of feelings.

A study published in the Journal of Research in Music Education discovered that children engaged in music education exhibited higher levels of empathy and emotional intelligence. The collaborative nature of playing in an ensemble cultivates a sense of camaraderie, teaching children the art of listening and responding to the emotions conveyed through music.

The Social Symphony:

In the grand performance of life, the ability to collaborate and communicate is key. Music education, with its emphasis on ensemble playing and group dynamics, becomes the rehearsal ground for these essential social skills. You will find resonance in the transformative power of music education to tip the scales in favor of positive social development.

Research from the National Association for Music Education highlights the social benefits of music education, noting that children engaged in musical activities develop a strong sense of teamwork, discipline, and leadership. The shared pursuit of musical excellence cultivates a sense of belonging, transforming classrooms into harmonious communities.

Conclusion:

In the symphony of a child’s education, music is not merely an optional chord but a fundamental note that resonates across the cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions. Let us acknowledge that the true crescendo of a child’s potential is orchestrated by the transformative power of music education. It’s not just about creating musicians; it is about sculpting minds that resonate with the harmonies of lifelong learning and emotional intelligence. The importance of music education, when understood in this comprehensive light, becomes a powerful testament to the enduring melody that shapes the future of our young minds.

As the holiday season approaches, finding the perfect gift for your young guitar player can be challenging. To help you out, we’ve compiled a list of the top 5 holiday gifts based on consumer and expert reviews.

1. Music lessons:

Music lessons provide a unique and lasting experience that fosters creativity, skill-building, and personal growth. Lessons can ignite, or re-ignite passion and help beginners start their creative musical journey. Additionally, music lessons offer a chance to connect to a mentor and join a community, making a thoughtful and engaging gift!

2. PRS Headstock Tuner:

Stay in tune easily and in style with the PRS Clip-On Tuner.

https://www.simsmusic.com/prs-headstock-tuner.html

3. Ernie Ball Musician’s Tool Kit – Best Tool Kit:

Ernie Ball’s all in one tool kit is perfect for cleaning, maintaining and keeping your instrument in perfect playing condition. Change strings, set intonation, adjust the action, check string height and more. Tool kit includes Microfiber Polish Cloth, Wonder Wipes, Heavy Duty String Cutter, Peg Winder, 6-in-1 Screwdriver, Ruler, and durable Hex Wrench Set.

https://www.ernieball.com/guitar-accessories/guitar-instrument-care/tools

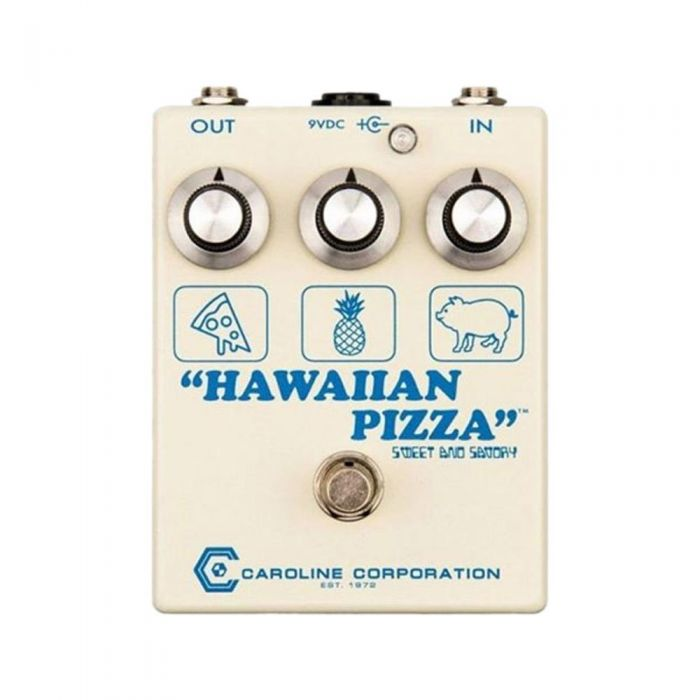

4. Caroline Guitar Co. Hawaiian Pizza pedal:

A bespoke artisanal blockchain of handcrafted tone, the sonic equivalent of a forbidden delicacy, all from just three knobs and the truth.

https://carolineguitar.com/product/hawaiian-pizza/

5. A new guitar from Sims Music

What young guitarist wouldn’t love a new guitar? Our partners at Sims Music have an incredible selection for every style and budget with an extremely friendly and knowledgable staff, there to help you make the best decision that will absolutely put a smile on your young guitar player’s face!

https://www.simsmusic.com/products/guitars/electric/

These gifts cater to different needs and skill levels, offering a well-rounded approach to learning and enjoying guitar playing. Whether it’s lessons, accessories, or a new guitar, your young guitarist is sure to be delighted with any of these thoughtful gifts.

Every musician loves overcoming a challenge, and with drumming, a challenge is more than a sore throat or blisters from plucking strings. It takes a toll on your entire body—legs for the kick and hi hat, arms for the snare, cymbals, and toms, neck for headbanging—which means a challenge is as broad as music genres.

Here are five songs to challenge your skills and push your limits as a drummer in a fun, exciting way.

Brianstorm is a powerful opener to Arctic Monkey’s album Favourite Worst Nightmare with a quick and heavy drum beat in the beginning that flies around the kit, transitioning swiftly into the first verse with a rapidfire hi hat that is dizzying to follow. This 2:50 minute song never never slows down, so it can be a great way to test out your arm and wrist strength. Although it seems like a simple enough beat, it’s the speed that truly makes it a fun challenge to tackle.

Starting strong with some double pedal action, this Van Halen song takes funky, offbeat rhythms and meshes them into a high energy classic that is sure to rile up any crowd. Hot for Teacher takes a lot of energy, physically and mentally, in order to power through. Although it might take some time to adjust to two pedals, once you’ve memorized all the stops and pattern changes, it’ll be smooth sailing for you there.

Moby Dick is misleadingly easy at first, with a simple, jazzy tone at the beginning, but its simplicity is what makes it so challenging. It consists almost entirely of drumming, which means you get the spotlight. With sudden, fast movements that are sure to make you trip up during every listen, this Led Zeppelin song gives plenty of breathing room to be creative with your own fills—which in and of itself is a challenge—but also grants you bragging rights if you manage to memorize it.

This Mars Voltas song is bound to make any intermediate drummer have a heart attack out of pure intimidation. A loud, eccentric banger with lots of stops, it becomes simpler in the verse, but maintains that fast-faced energy all the way through. Not to mention Goliath is also over seven minutes long, no doubt testing any experienced drummer’s energy levels with just one playthrough, but is also a satisfying beast to tame.

Another song that leans less on speed and more on disorienting beats that are hard to keep up with, Ticks & Leeches is 8 minutes of rock and metal ups and downs, giving pauses in between verses to grant you a break every now and then before diving straight into another fast, harsh chorus. If you’re a huge Tool fan with enough time to dedicate to learning every second of this, it’s a great song to push yourself to your drumming limits.

Let me begin by saying that I completely respect a parent’s authority and (as a parent myself) that a parent’s decision is absolute; however, I would like to challenge the idea that ceasing lessons is the best answer to academic “rough spots.”

Music is Education

Music lessons are too often ranked low on the totem poll in comparison to academics, sports, and other school-related activities. I am a strong believer that music is a very important part of general education. There are countless studies that support music’s positive impact on the mind and learning. Music is, and should be, classified simply as education. The most successful students I teach are well-rounded individuals educated and trained in academics, physical activity, and the arts.

Music Can be a Career

My dad once told me I was living a pipe dream by trying to succeed in music. He actually kicked me out of the house because of the differences in our outlooks. Nowadays, he’s my biggest fan and has apologized for not believing in me. There are so many avenues for students to make a legitimate career in music. Like any trade, if you do good work, you will be successful; how successful is up to the individual. It is my hope that parents will start appreciating its validity and not trivialize music as only a hobby that accompanies your “real job.”

Strengths and Weaknesses

There are some students at our studio who are extremely gifted and passionate about music. In some instances, it is one of the few areas in which the student excels. Many parents believe that taking away something that their children love and are passionate about will make them more focused on their school work. I would argue against that line of thinking; if they love it and are passionate about it, and it is education (see my first point), then perhaps it would serve the child better to pour more into it. Music may actually be the most viable career for some of these students.

Mentoring

At Freeway Music, we instructors highly value the mentoring aspect of our jobs. We not only teach students how to play, but we also ask them about their weeks and their schoolwork, encouraging them to do better, instilling professionalism and responsibility into them, and more. This mentoring is vital in children’s lives. Rather than removing the lessons, what if you had a meeting with their private instructor (who often has heavy influence on the student) and ask them to help encourage the student to improve in school as a way of showing how serious they are about pursuing their passion for music? Use this passion to fuel their academic pursuits.

Alternate Punishments

When it comes to removing distractions that can be leveraged as privileges, there are more appropriate things to remove from a child’s life than music lessons. What about phones, tvs, tablets, computers, going out with friends, dessert, cars, etc.? Surely there are some pretty strong bargaining chips beyond music lessons.

At the end of the day, music is a form of education that can help make a student well-rounded and perhaps propel them to a career. Music instructors provide a service that includes one-on-one mentoring. I must say again, I completely respect parental authority and the parent is final arbiter. I just ask that you consider these points I detailed above and challenge your preconceived notions that music lessons are expendable.

You just had a great lesson, and are packing up to leave your teacher’s studio when he/ she says those all-important, gut-wrenching words: “Practice a lot this week!” Good practicing habits are difficult to form, especially if you’ve heard the saying, “Practice makes perfect,” which is not true! Practice doesn’t make perfect- it makes permanent.

So, how do you make the most of your practice time and make progress on your music? Here are a few tips for making practice time productive, efficient, and more enjoyable that apply to beginners or experienced musicians!

1 – Prepare your practice space

– Have a regularly scheduled time set aside for practice

– Free the practice area of any distractions not needed for practice: snacks, TV,phone, electronics, etc.

– Always warm-up first (flash cards, scales, app/review, etc.) if even for a short time!

2 – Have a plan- “what needs work today?”

3 – Don’t simply play through each piece from beginning to end- be diligent and work out the trouble spots. (Just ‘playing’ through songs isn’t true practicing.)

4 – When something is hard, think: “What is the melody?” “Am I in the correct hand position/on the right notes?” Practice hands separate and figure it out.

5 – SLOW-motion practice- practice under tempo- not fast! Especially with a new piece, play it slowly to get the correct fingering, rhythm, and notes correct before playing it up to performance tempo.* (*this is not super fun at first, but saves a lot of headache from wrong notes/rhythms later!)

6 – Reward yourself- if you accomplished your goals and practiced well, have fun and play through some old music or mess around with a new idea! You deserve it.

7 – Set goals, stay focused, and leave your practice session hearing a difference in your music! (Your teacher will be super excited, and your parents will be so grateful you don’t have to keep playing the same songs over and over…plus, you will enjoy the benefits, too!)

Practice doesn’t make perfect, but it does make permanent. Take the time to do practicing the right way and you will notice the difference in your lessons and in your music!

You may like these blogs:

How to Develop a Positive Practice Cycle

Completing the Circuit

Every so often, a parent of a student will make a comment or ask a question that just sticks with you. For me, that happened as I was getting ready to write this post. I casually mentioned my topic of choice which, up until I spoke with this parent, was going to be insight into what happens in beginning piano lessons and why X was critical in developing Y…how academic. The parent commented, “I would love something on what our jobs is as parents,” and I referred her to my more recent post on practicing tips for parents, but her comment stuck with me. It’s stuck in my head so much that I think the real question is, “what is it that you do as a private teacher and how do I help my child progress?”

For a parent, I have to imagine our jobs seem somewhat vague and the gauge of progress is marked by recitals and practice time at home. Ask us how your child is doing and we will usually say something positive, in some instances offer some more critical feedback, and usually try to sum up the lesson that week in thirty seconds as we end one lesson and begin another. Sometimes we email or make calls, but we rely heavily on the ever present notebook, markings in the music, and, most importantly, sending the student home knowing what they have to do. So, what is it that we private teachers do and where do you fit into all of this?

The first thing to address is that we couldn’t be more different from public school teachers. Attire and atmosphere aside, there is no cut and dry curriculum, no single set of standards to which we teach, no marker of passing or failing, and no singular way that any one student is taught. It is perhaps the greatest blessing and greatest curse of the private teacher and our relationship with parents. We are often minimally concerned with parents reinforcing our roles since we work directly and individually with each student one at a time within their own capacity. We gauge success on interest peaking and technical achievements that there simply isn’t a way to easily define. We rely on ourselves and our individual approaches to help each student move forward and build a positive relationship with playing their chosen instrument. As a parent, you may be left wondering, “where does that leave me and what do I do?”

It leaves you confused, but there’s a very good reason and that’s because we all came through the American educational system of quantifiable results, standardized testing, and a constant progression of learn this, then this, and then you will know that. Leaving out any mention of what is happening in education today, the history of this model is fairly recent. Believe it or not, our structure and system of education is modeled after the assembly line pioneered by the Ford Motor Company. Now, if you reflect on your own education, no matter the shifts that occur nearly by the decade, you will see that this model fits perfectly around how we were taught to learn and how progress is measured. Think of the diploma upon graduating high school as a representation of the car you just completed and college the road you will travel finding your way in academia. Concurrent to trends in public education, we private teachers were there all along, teaching our instruments and, while we evolved over time – becoming more modern using technology, offering less traditionally classical educations – not much has changed in the sense that the goal is to get you to love to play and to play well.

You may have noticed that I still haven’t answered where you, the parent, belong in all of this and how you might help your child succeed. The fact is, you can Google that and there will be tons of private teachers and academics out there who will offer a wide array of suggestions, make up fanciful games, suggest using this bit of technology or that, but I’ll offer you what I believe the truth is: you know your child better than we do. We can offer suggestions on what to do at home; we can offer advice on how you should never, ever force someone to practice; we can remind you that the love of practicing is built over years, not months, but that a positive relationship to music should be maintained at all times. There is no singular magic fix to make someone love an instrument faster or to get them to practice or play more. You know your child and their interests, their attention span, and you have to find a way to get those to work together with music making until playing is a brand new and personalized interest. That’s exactly what we do in private teaching. The parent that I spoke to earlier said her son loved performing, but practicing was having its ups and downs. I made a suggestion for a fun practice idea, but will it work? I have no idea. All I can hope is that if it doesn’t, maybe that will inspire a new idea at home.

We try our hardest to engage each student and we rely on you to be our cheerleader. We tell you things that seem to feel so contradictory to what you feel like should happen – how practicing can’t be treated like homework and it doesn’t just ‘get done’ or how it is completely fine that they only played their piece three times that week and we’re so thrilled that we can shoot for four times next week. We tell you it takes time and it does. If you want to know what the best day in private teaching is, it’s the day that a student asks their first real musical question based on inference. Those are the days I live for even if they didn’t practice that week.

Other articles by David J. Pacific:

Stop Asking Your Child to Practice

“Beware of the Bark Side!” or Digital Pianos

“This One Looks Nice!”Setting the Stage for Piano Purchasing Prowess

The It’s a word we all fumbled over as we began to read aloud as kids. Most of our words work phonetically from the alphabet that we learn. Teachers and parents patiently waited as we sounded out “r-u-n” or “j-u-m-p” in our first reading encounters. There came a time, though, when “sight-words” were introduced. Which is why, at the beginning of this paragraph, you heard the word “the” in your head as you read and not “tuh-heh”—which would be the literal sounding out of the word. At some point, we also learned how to spell the word “the,” realizing in the process that it looked nothing like what the phonetic equivalent would be.

Music is a language.

Approaching the aspect of rhythm from a linguistic point of view by expanding your vocabulary of rhythmic “sight-words” can make speaking music a much more instantaneously satisfying and simple process. Getting to the point of being able to consistently speak/tap/play a specific rhythm correctly without having to count through it (i.e. sound out the word). This process of learning “rhythm sight-words” may only involve a measure—or it may involve an entire phrase. Internalizing patterns so they can be easily “spoken” (played) allows you as a musician to read quickly, understand poly-linear rhythms (two different patterns happening at the same time), use patterns in improvisation, incorporate new rhythms into your song writing, and learn music by ear with pattern recognition.

Hooked On Rhythmics

As a pianist, I often separate rhythms and pitches for beginning students learning how to read. Sometimes when I encounter a new piece, there will be times that I simply pat out or speak rhythm patterns before attempting to play the piece. Here are some tips for growing your vocabulary when it comes to “rhythmic sight words.”

1) Isolate small sections of rhythm that you’re either drawn toward or fumble over. Start with a measure that trips you up or a section of a riff in a song that you find yourself tapping or humming.

2) If reading rhythms, count out loud and work with a metronome to ensure that you’re playing them correctly (you don’t want to be playing a rhythm incorrectly for the rest of your life…haha). If you picked a section of rhythm by ear, make sure you can play/speak/tap it accurately, and then write out the rhythm that you picked, making sure it lines up with the original recording. The first time you do either of these things, you may need to work with a teacher who can guide you through it—it’s also helpful to have someone double check accuracy. Remember that everything takes a little longer the first time and gets easier with repetition—think about the first time you read a sentence aloud.

3) Once you’ve gotten totally comfortable with the pattern, play or sing it in context. As a pianist, I often play multiple lines, so I attempt the rhythm in conjunction with the other lines that are supposed to be played simultaneously.

4) Take and find the pattern out of context. Try playing scales, arpeggios, or new ideas in that rhythm pattern—this is a great way to keep warming up from being boring! Find the pattern in other pieces of music, whether through listening or reading, and explore ways to use the patterns in other songs. Maybe use the pattern in your own songwriting.

Finally, remember that music is a language and that to be fluent in any language the skills of conversation, reading and writing, are non-negotiable. Work for fluency so that you can express yourself fully and easily in your music! You’ll be amazed at how this takes the fun of playing music to the next level.

Kate

Other blogs by Kate:

New Year’s Resolution From a Pianist: Part 1

New Year’s Resolution From a Pianist: Part 2

New Year’s Resolution From a Pianist: Part 3

Through teaching and running Freeway, I’ve had many opportunities to hold and attend a lot of great songwriter clinics. So, I want to share some of the best advice I’ve learned about songwriting.

“A song is a snapshot of time” ~Tom Conlon

This is such an inspiring statement and so very true! Music is an amazing art form. Most people attach sound to music, but seldom visual art. Words and lyrics create settings and paint pictures in listeners’ heads. The music evokes certain moods. Certain lyrics will reflect the culture of the time period in which they are written. Various music styles move with time as well. Since culture will always continue to change and evolve, lyrics can be fresh forever. Just look Sam Cooke’s “Change Gonna Come”. It’s clearly about the civil rights movement. Songs are a “snapshot in time” and it’s almost our civic duty as writers to capture these moments.

Check Out Tom Conlon’s Music Here.

“Make songwriting a Ritual.” ~ Danielle Howle

To master writing, you have to maintain the attitude you would with anything you would master. You have to stay the course and practice writing. One of the toughest parts about working out is getting yourself in a routine. You have to be intentional and set aside time to write everyday. Get into the ritual of songwriting. If you are prolific, you are bound to have some gems in there. Also, don’t be too hard on yourself. Not ALL of your songs will be amazing. I am a huge Beatles fan. They wrote a ton of tunes and they have a lot of songs that I don’t like at all. You can’t have the cream of the crop without a good sized crop.

Check out Danielle Howle’s Music Here.

“If you aren’t writing, you aren’t living.” ~ Tom Conlon

Yes. It’s the second time I’ve referenced Tom Conlon, but he is a very wise man. If you aren’t filling the tank up, how do you expect to put anything out? It’s the same as any endeavor in life. Take a trip out of town, watch a movie, read a book, listen to new music, go to a show, or take part in any other activity to create some new life experiences. If you aren’t experiencing life, you will not have anything to talk about. You will be amazed at how inspiring it will be.

Hopefully, these pieces of advice will aid you in being a better writer as well. Always remember the importance of your art, make it a priority, and live a little. Until next time, happy writing!

More Songwriting Tips: